Global heating over this millennium could exceed previous estimates due to carbon cycle feedback loops. This is the conclusion of a new study by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK).

The analysis shows that achieving the Paris Agreement’s aim of limiting global temperature rise to well below 2°C is only feasible under very low emission scenarios, and if climate sensitivity is lower than current best estimates. The paper is the first to make long-term projections over the next 1,000 years while accounting for currently established carbon cycle feedbacks, including methane.

“Our study demonstrates that even in emission scenarios typically considered ‘safe’, where global warming is generally considered to remain below 2°C, climate and carbon cycle feedbacks, like the thawing of permafrost, could lead to temperature increases substantially above this threshold,” says PIK scientist Christine Kaufhold, lead author of the paper published in Environmental Research Letters.

“We found that peak warming could be much higher than previously expected under low-to-moderate emission scenarios.”

The study projects the long-term impacts of human-induced climate change and underlines that even small changes in emissions could lead to far greater warming than previously anticipated, further complicating efforts to meet the Paris Agreement targets.

“This highlights the urgent need for even faster carbon reduction and removal efforts,” Kaufhold says.

Most studies are too short-term to capture peak warming, as they end by 2100 or 2300. By running longer simulations and incorporating all major carbon cycle feedbacks, including the methane cycle, the researchers were able to assess the potential additional warming from these feedbacks and estimate the possible peak warming.

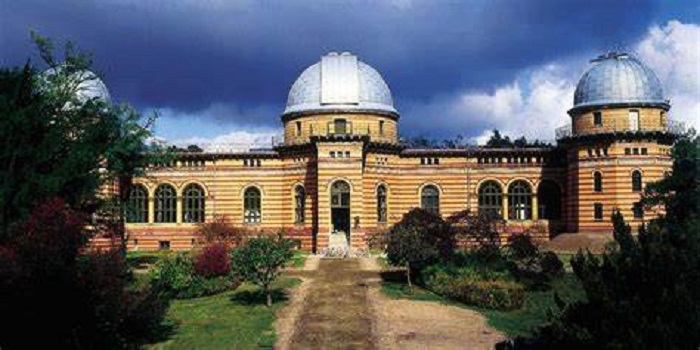

The team used PIK’s newly developed Earth system model CLIMBER-X to simulate future climate scenarios over the next millennium under three low-to-moderate emissions trajectories – pathways that align with recent decarbonisation trends. CLIMBER-X integrates key physical, biological and geochemical processes, including atmospheric and oceanic conditions. It also represents an interactive carbon cycle, including methane, to simulate how the Earth system responds to different climate forcings, such as human-made greenhouse gas emissions.

Climate sensitivity shaping future climate outcomes

The study’s simulations consider a range of equilibrium climate sensitivities (ECSs) between 2°C and 5°C, defined as “very likely” by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The ECS is a critical measure in climate science, estimating the global temperature rise associated with a doubling of CO₂ concentrations.

“Our results show that the Paris Agreement’s goal is only achievable under very low emission scenarios and if the ECS is lower than current best estimates of 3°C,” says PIK scientist Matteo Willeit, co-author of the study. “If the ECS exceeds 3°C, carbon reduction must accelerate even more quickly than previously thought to keep the Paris target within reach.”

The paper highlights the important role ECS plays in shaping future climate outcomes while revealing the risks of failing to accurately estimate ECS. It emphasises the urgent need to more accurately quantify this metric and better constrain it.

“Our research makes it unmistakably clear: today’s actions will determine the future of life on this planet for centuries to come,” submits PIK director Johan Rockström, co-author of the paper.

Rockstrom adds: “The window for limiting global warming to below 2°C is rapidly closing. We are already seeing signs that the Earth system is losing resilience, which may trigger feedbacks that increase climate sensitivity, accelerate warming and increase deviations from predicted trends. To secure a liveable future, we must urgently step up our efforts to reduce emissions. The Paris Agreement’s goal is not just a political target, it is a fundamental physical limit.”