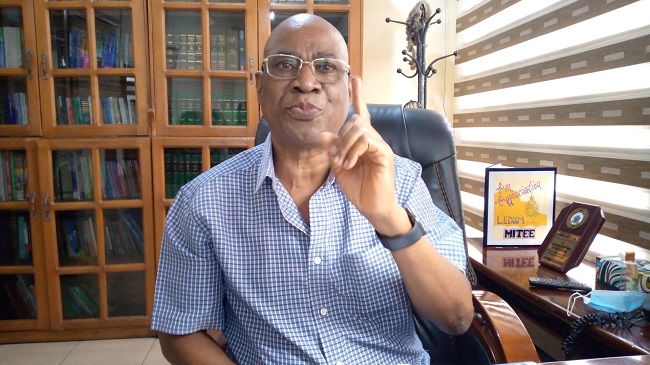

Ledum Mitee is one of those who broke the culture of silence on environmental pollution and the impunity of international oil corporations in Ogoniland, a tiny cluster of oil-rich villages south of Nigeria. He narrowly escaped execution 25 years ago when activist and playwright, Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight Ogoni leaders, who were at the vanguard of the struggle, were hanged by the military government after being convicted over allegations of murder. In his law chambers in Port Harcourt, River state, Mitee reflects deeply on the 40 years struggle over which the blood of his kinsmen and women was spilled and the country’s lack of political will to serve justice for his people and those in the Niger Delta. Interview by ABIOSE ADELAJA ADAMS, Bertha Fellow.

The environmental rights activism of the Ogonis is a very well told story, but could you please do a little bit of recap?

Ledum Mitee: I am one of those who were at the very beginning of that movement. I come from Kegbara-Dere, usually abbreviated as K-Dere, a village in Gokana local government area which has around 54 oil wells. K-Dere is known by Shell and the oil companies as having Bomu oilfield. When you talk of Ogoni oil, K-Dere accounts for almost 70 percent of the oil. It is when we thought that the devastation caused by oil exploitation was threatening the very existent of livelihoods of the people that led to the formation of Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP).

In fact, the meeting that culminated in that first Ogoni day in January 1993, was held in my village house (in K-Dere). From there we took a decision to match peacefully, carrying leaves to symbolise the vegetation that was being exploited and degraded. After that we were visited with a lot of repression. Several people were killed in the course of our campaigns.

There were 2000, which is 2 percent of our population at the time. The military occupied the place (Ogoni) eventually, we got severally detained, that is, I and the late Ken and others. We were eventually tried. We stayed 19 months in that detention at the military barracks called Bori camp here in Port Harcourt; maybe occasionally we were being taken to other places; eventually Ken and eight others were executed. I was lucky to have escaped that execution.

How did you escape?

Ledum Mitee: At the end of the day they said they didn’t find me guilty. With the benefit of hindsight, I think in the face of local and international pressure and outcry at the time, the military government felt ‘let it not look as if they wanted to kill every person,’ so eventually six were set free out of 15. The pattern in that execution is this: In MOSOP, I was number 2, Ken was number 1, so they eliminated that level of leadership and I was spared. In the youth wing, they didn’t get the number 1, so they killed number 2 and left number 3. If you look back now that appears like what they did… apparently, let’s take off the first level of leadership and other might be intimidated and scared.

That is what happened; and the struggle had been, as the name of the organization implies, the survival of the Ogoni people. Justice for the Ogoni people. How do we have a safe environment, and not that which has devastated the very social fabric of our society? We (Ogonis) feared that if we didn’t do anything the whole Ogoni might be extinct.

As someone who was there from the very beginning, do you think Ken Saro-Wiwa was rightly killed for the murder of the Ogoni four?

Ledum Mitee: If you ask me, I will say that was the excuse for which we were hounded. My theory is that both the Ogoni four and the Ogoni nine were set up and murdered by the government using one as the reason for killing the other. I hold the military government responsible for murder of the four and the other nine.

Looking at the Ogoni and Niger Delta today, would you say what Ken and the others died for has been addressed?

Ledum Mitee: Absolutely not. And that’s a shame. Despite the sacrifices that we made. Despite what has been acknowledged as one of the most peaceful, nonviolent struggles; and for which we were killed, we found that the government has not thought it wise to visit those demands in the bill of rights in any positive way. Rather, they visited it with violence which in turn has been responsible for the violence witnessed in the Niger Delta today. Sometimes I am confronted by some people who opted for armed struggle against the authorities. And they ask me why I still preach non-violence? They say you people did non-violence and you were killed that is why we are opting for a violent action. So it is the negative response to our nonviolent demands that precipitated the violent struggle that engulfed the Niger delta today.

If you say the agitations of the Niger Delta have not been addressed, what about the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC) and the ongoing clean up in Ogoniland?

Ledum Mitee: Absolutely not. You don’t scratch people where it is not itching them. I personally was involved in the struggle that led to the OMPADEC (Oil Minerals Producing Area Development Commission). At that time as the name implies, it was targeted at the oil mineral producing area, not the Niger Delta — which has even been politicised now. When by the time Obasanjo came to power, the issue of the Niger Delta was on the front burner even in the world. Especially following the execution of Ken and the others. I know that I personally engaged the government of Abdulsalami Abubakar. And through our interactions with him, we helped in making suggestions. And I am always feeling quite impressed with what they did. They came up with their own OMPADEC Decree. That decree provided that the commission created by that decree was to be responsible for the oil producing communities according to the priorities set by those communities. And we went forward to say that each of those communities to set up a community development committee (CDC) that will now generate projects of their own priority. It is these projects that the commission will now focus on. In other words, a bottom-up approach was adopted. When Obasanjo came in, he repealed that law and created NDDC. Under section 7 of the NDDC, it came to now deal with the Niger Delta in a larger way.

I just think that they (government) wanted to do something that they (the international observers) will say we are responding to the agitations of people of the Niger Delta region. And now in section 7, they gave the commission the powers according to the priorities set by the presidency. And in fact, under section 7 subsection 3c, it clearly said that in carrying out these functions, the NDDC should act according to directives, supervision, control of one person —the president. So you now made the NDDC an agency to be controlled by the president and commander-in-chief. In such a situation, that is where you see all these corruptions coming from. It has now become a patronage machine of whoever sits at the presidency. That is why we hear all these stories that are so shocking. How many people in the Niger Delta will say that their lives have become better because of the NDDC? When you see the sort of project that we saw on TV; that they were buying face mask for almost a half a billion the Nigerian police. You wonder… how much is a face mask? (Laughs)

Are you saying the NDDC does not address the needs of the people of Niger Delta?

Ledum Mitee: Absolutely not. How many people in the Niger Delta will say that their lives have become better because of the NDDC? Everything about it is directed to the patronage of the party at the centre. It is like an ATM (automated teller machine) of the presidency. The truth is that it has become how they fund the party and elections. It is from the centre (presidency). So elections in this part of the world are funded through the NDDC, for the party at the centre. In fact, someone was saying and I don’t think I should doubt that; that without NDDC, APC (All Progressives Congress, Nigeria’s ruling party) will hardly exist here (in Rivers state, ruled by the opposition). It is the same thing as when the PDP was in power, it was also funded from NDDC. That is exactly how an outfit like that works. So how can such a body deal with the issues of the woman who needs water in her village or roads that we cannot pass?

How then can NDDC respond to the needs of the Niger Delta?

Ledum Mitee: Even if we look at it in analysis, the whole idea of the NDDC is based on confusion. Because, when you talk about the Niger Delta issues, you are dealing with two issues. One is the issues of a fragile terrain, which is different from oil pollution. It is separate and distinct from oil producing issues. The Niger Delta issue has always been before Nigeria’s independence because communities in this area, owing to their terrain, are fragile. There are some parts of this area that before you can even build a road, you will first build land. To build one kilometre of road here, takes huge resources, so you need affirmative action. That is the classic Niger Delta issue. The issue of the fragile terrain and ecosystem of Niger Delta that you need affirmative action to check. The second issue is that of oil pollution. So, when you create the NDDC to address these two problems as one, people are now seeing it as one issue (laughs). It is like someone who has malaria and typhoid and you use only one medicine. That is why the whole issue called NDDC is not working and not intended to work.

Should NDDC then be scrapped?

Ledum Mitee: You will not say because plane has crashed, so we will now trek. Let’s go back to the fundamentals. The national assembly should stop wasting time with all these (investigations). Yes, they are throwing up the issues, but as you see, corruption is always federally driven and they (presidency) are the people who has the powers to check it. Who controls the police? Who arrests the people who are corrupt? Who controls the EFCC or ICPC? What we need to do as I said earlier, I have given you two options — one is the Abdulsalami Abubakar option of bottom-up approach, given that mandate to develop according to the priorities set by the communities. Let’s go back, change the law and let’s go back to that model. And then rather than scrapping it, we should depoliticize it, make it less bureaucratic and change the structure in a manner that can actually respond to the needs and yearnings of the people that is intending to cater for.

What can you say about the clean-up currently ongoing in your land?

Ledum Mitee: My view is that there is no clean-up going on. It’s a cover up. Ask any person you see in Ogoni if they have seen any drop of oil spilled in those places they said they are cleaning up. Most of those sites are places where there has never been any pollution. The real places of pollution has not been touched. So, it’s a scam. It’s just something to show that we are doing something. The idea is to show that we dig a place where nothing is happening. After a while, we call experts to come and check and they will say it’s clean. Meanwhile the main places that are polluted are untouched. And you see that is not anything you call a clean-up. By clean up you go to the area where there is real pollution and start that process.

Emergency measures such as providing potable drinking water ought to have been provided before clean up. But several of the impacted communities I visited said this has not been done…

Ledum Mitee: When the UNEP released its report, there are certain fundamentals it said, in fact, it called them emergency measures. One of it is that our people were drinking water that was 1000 times above the acceptable level anywhere in the world. UNEP said that people should not drink those water again, in fact, they should not bathe in the streams or fish there. Years after, that is the only water available. That’s where we are drinking and fishing. And yet those are emergency matters. Another thing is the artisanal refineries. If you read the UNEP report it said they should provide $10 million for the purpose of proving alternative employment for those people who are engaged in artisanal refinery.

Because you cannot be doing pollution through artisanal refineries, and then you are cleaning. You must deal with those issues. Also, Shell must decommission its wells in the land. These are the fundamentals that they said they must do, but none of these have happened. But they are doing something so that they show that they are doing something. I am one of those people who are not fooled by that. It’s just the same thing, giving jobs to the boys, political patronage. I read an investigative report that some of those companies don’t even have experience in clean up, but they give the contract to several of their party people. It’s a shame because it is on the head of our people that they are doing all these and on the lives of our people and that is what pains me. Because I am one of those people that agitated for this. In fact, even when UNEP came here, I held a meeting with the head of UNEP in the whole world and decided what should be done.

What do you think of HYPREP?

Ledum Mitee: How can that deliver when you have some board where you have a sprinkling of Ogoni people, and then the oil companies and the government are the majority, in fact, the overwhelming majority? In that case, even with the best of intentions, two or three Ogoni people will carry their hands up, (but can’t have a voice). Unfortunately, even the Ogoni members of the board are enveloped. They have not given the Ogonis the effective voice and representation. How can they have a voice? Yet those people (Ogonis) are the victims. They are the people whose voice should count but they are been marginalized.

Do you agree with those that say Shell should not be part of the board?

Ledum Mitee: Have you seen what’s going on, Shell staff, one Dr. Philip, has been the person in charge of what Shell called remediation in the past. All of a sudden he is out of Shell and what did they do? He is now the director of operations in HYPREP. How can such a person become the director of operations when you were part of the problem? This was the same thing that happened when we wanted to meet with UNEP. And what did we find? The person who was supposed to be the lead person in the project was actually a former Shell staff. I protested vigorously and they removed him. Those are the things we are talking about; because if you are going to do a transparent project, you must not put those that were directly involved with the problem. You can be on the board where other people are.

What is your take on government’s effort at stopping artisanal refinery which is causing even more pollution at the Niger Delta?

Ledum Mitee: I was chairman of NEITI (Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative) until 2015. And as chairman, I sat on the national economic council committee on oil pipeline vandalization and oil theft. I actually chaired its subcommittee on community engagement and sensitization. That took me to almost every community in Niger Delta where this kind of bunkering is taking place. I engaged with some of the youths involved. And they clearly told me that they were opening up to me not because I was a member of the federal government delegation, but because of who I was. So, they believe that they can tell me the truth and they did. What came out is the level of complicity between what you call the security agencies and those who are refining. One young man told me a story.

Up till today, it is my classic of how I can describe what is going on. He told me that he has the capacity to dive up to six metres deep into the river, cut pipe (and tap crude). Shell recognized that he was such a threat and begged him that they will be paying him N500,000 a month. He accepted. One week after, the MJTF (military joint task force) called him and told him “that you, if Shell don pay you abi, if you don’t go back and do this thing that we have all been benefitting from, we will put you on national television”. So, he said he got back because he doesn’t want trouble.

Knowing this is an illegal business, are you in support of this?

Ledum Mitee: How do you discourage people who left school, and five years after, they have not attended any job interview; a graduate who now sits in his village and does this business and in a week can make a million. How do you tell such a person they should leave the business? We did some rough work on artisanal refineries some years ago which showed that, that economy employed about half a million people in Niger Delta and the GDP is about three times the national average.

My committee came up with a report that if you want to protect oil pipelines, then the communities must benefit, so that they see the reason why they should partner with you against those who want to cut the pipes. [My recommendation was that] if pipelines passes through my community, then we say bring youths who will guard these pipelines, pay them living wages and then alternate them for period of six months; and then say if you are able to organize like that; and after six months you do not see your pipeline been vandalized, you will get so and so project worth this much. That community now has an incentive why they should help — the youths are engaged, the community gets a project, every person now sees a benefit why they should allow the pipelines flow. But now, the communities are not benefitting, they are seeing these boys doing the thing, it pollutes their yams, it pollutes their farms, but they do not see any incentive.

Even if there is anything they want to do to report the vandals, they see these same boys with the soldiers and law enforcement agents, which they are supposed to use against them. So, the community is dis-empowered. They are the victims of all these. If we don’t understand that that level of complicity goes then we have not started. And Nigeria doesn’t seem to care. The only time they care is when our production figure is less than the expected figure.

Why has government not heeded the report of your committee?

Ledum Mitee: It’s like asking why are we the way we are in this country? (laughs) The Nigerian factor. I have said this at several fora. I still believe this is the solution.

Why is it difficult for Nigeria to implement environmental protection laws?

Ledum Mitee: In Nigeria we have laws. In fact if you ask me the country is over-lawed. Like one French philosopher said years ago. He said when I go to a country, I don’t ask whether there are laws in their books, I ask them how they are implemented. If the law says thou shall not steal if you steal you will be jailed. And then ten people steal and nine people go free. That is the law! The law says thou shalt steal. In other parts of the world, if ten people steal and eight are caught, all of them will sit back. You will be amazed at how things are gone wrong and nobody is held accountable. For instance, the NDDC, has anyone been held accountable?

What is justice for the Ogonis?

Ledum Mitee: Justice for the Ogoni people is when they have a safe and clean environment that is free from pollution. Justice for the Ogoni is that if they shout they will not be killed unlawfully. Justice for the Ogoni people is they get a just recompense from the resources that come from their land for their development. These are the issues and it takes a government that is committed to justice to dish that out. Unfortunately, I have not seen that yet.

Originally published in The Cable

This is one in a series of reports on the Nigerian environment, supported by the Bertha Foundation