CustomMade, an online marketplace, discloses in this treatise that though illegal logging costs the global economy an estimated $30 to $100 billion in lost revenue annually, the mass exodus of our forests has more devastating, long-lasting implications, putting the environment, politics and social stability at risk

Many of us make daily choices to try to live more environmentally conscious lifestyles. But there’s an element probably present in everyone’s home that’s contributing to the destruction of the natural world: items made from illegally sourced wood. The paper sitting in your printer, the toilet paper in your bathroom, and the coffee table in your living room may all come from illegal logging operations. Each year, more than 32 million acres of forest are illegally and unsustainably logged.

Many of us make daily choices to try to live more environmentally conscious lifestyles. But there’s an element probably present in everyone’s home that’s contributing to the destruction of the natural world: items made from illegally sourced wood. The paper sitting in your printer, the toilet paper in your bathroom, and the coffee table in your living room may all come from illegal logging operations. Each year, more than 32 million acres of forest are illegally and unsustainably logged.

Illegal logging – the harvesting, transporting, processing, buying, or selling of timber in violation of national laws – is a global issue, affecting most forested countries. The term also includes wood harvested from protected areas or threatened species of plants or trees as well as the falsification of official logging documents, breached license agreements, and corruption of government officials. Because of the natural of illegal logging, it’s also difficult to measure the scale of the devastation. “Most of it is selective logging, not big clear cuts,” says Dr. Matt Finer, Amazon Conservation Association’s research specialist. The pick-and-choose method makes it extremely difficult to spot missing trees in aerial pictures or satellite imagery.

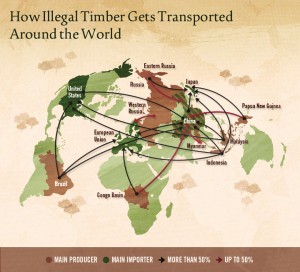

Illegal logging runs rampant in poorer nations and is dominated by organized crime. A 2012 U.N. report estimated organized crime groups were to blame for up to 90 percent of tropical deforestation. It takes place primarily in the tropical forests of the Amazon basin, Central Africa, and Southeast Asia. Currently, Indonesia is the hardest hit country; 40 percent of its 6.02 million forest hectares have been lost to illegal logging. Though a short-term law enforcement effort in the mid-2000s temporarily slowed the loss, illegal logging has increased in scale over the last three to five years.

The main, most obvious reason for illegal logging the high global demand for timber, paper, and other wood-derived products. But not all logged trees are turned into flooring, paper, and plywood. Around40 percent of removed wood is used as fuel for energy needs, including cooking and heating; in some tropical regions, that figure skyrockets to as high as 80 percent.

Corruption, economic and political instability, a lack of democracy, insufficient regulations, and weak governments all contribute to illegal logging. There are also insufficient penalty systems in place: A low risk coupled with high profit incentive makes illegal logging all the more enticing to those who need or want the money. Because illegal timber is generally less expensive and revenues are up to five-ten times higher, it’s hard for legal timber operations to compete.

The source of the wood is only part of the problem. Consumer countries contribute by importing wood without always knowing or checking if it’s been legally sourced. For example, the U.S. is ranked as the largest wood products market in the world. Translation? Many of us unknowingly purchase items made from illegally logged wood and keep the demand for inexpensive goods strong.

Illegal logging costs the global economy an estimated $30-100 billion in lost revenue annually – 10 to 30 percent of the total global timber trade. But the mass exodus of our forests has more devastating, long-lasting implications. It puts the environment, politics, and social stability at risk.

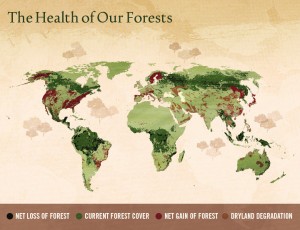

Clearing trees haphazardly decreases the chances for ecosystems to adapt to climate change and human contact. Research shows that for every commercial tree removed, 27 other trees are damaged, 40 meters of road are created, and 600 square meters of canopy is opened. Once trees are cut down, they are transported by tractor along the newly formed roads, which double as easy-access hunting routes.

Without dense forests to filter water and hold soil in place, soil erosion increases, and rivers and streams fill with sediment and debris, which has destroyed coral reefs and other aquatic habitats. Degradation of forests also destroys wildlife habitats on land, threatens populations of some of the most endangered primates, and jeopardizes plant biodiversity.

Logged areas are also susceptible to changing weather patterns as lost forest can make rainfall more erratic and consequently lengthen dry periods. Forest fires are another known environmental effect of logging: Clearing areas emits large amounts of carbon dioxide, which in turn becomes fuel for intense blazes. Many major forest fires worldwide were either started or worsened by logging or other agricultural development in otherwise pristine environments.

Illegal logging can also result in political conflict and clashes over land and resources. When the law is disregarded, community values are strained. “(It) undermines the entire landscape-level conservation strategy,” Finer says.

For many tropical countries, the conservation of forest cover focuses on the establishment of protected areas and indigenous territories, he explains. Once illegal logging bulldozes its way through these formerly protected areas, the system is destabilized. Local villagers and indigenous tribes are driven from their homes, face murder and violence, and are subjected to uncontrolled colonization. In July 2014, Amazon Indians – previously unconnected with the outside world – emerged from a Brazilian rainforest due to illegal logging.

For the forest-dependent locals that have thrived on tropical forestland for thousands of years, logging near and through homeland can result in scarcer quantities of food, building materials, and medicinal plants. Meat and fish have been compromised by hunting, habitat destruction, and polluted conditions. Logging companies have even bulldozed through gardens and other edible plants and trees that provide nutrients for native peoples. Oil runoff from machinery and chemicals used to treat timber also pollute the land and water supply.

Putting a Stop to Illegal Logging

Putting a Stop to Illegal Logging

Even if timber sports a single producer label, it’s often been traded many times during transport and could have come from an illegal location. For a logging operation to be legal, there are a number of guidelines a company must follow to cut, extract, transport, and sell timber. Along that supply chain, there are countless methods of breaking logging laws. Even timber marked as certified – and with a higher price tag – may not be.

Some laws, such as the Lacey Act, control logging in certain areas in an attempt to halt illegal trade. Unfortunately, they’re often broken. Even in countries like Peru where forests are protected by a modern forestry law as well as a free trade agreement with the U.S., some logging operations still operate illegally. “This mostly comes from providing false information in the annual management plant and claiming the presence of trees that don’t actually exist within the concession, so they can then use those permits to log timber elsewhere outside,” Finer says.

Most legal logging initiatives focus on promoting sustainable logging, with incentives for legal trade (like REDD+); they don’t address the widespread extortion, fraud, laundering, and bribery. For instance, the Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade Action Plan (FLEGT) was developed to reduce illegal import to the European Union. The key to the program is voluntary partnership agreements that ensure only legally sourced timber and products are imported into the EU from participating countries. Other major players in the legal logging game include the International Consortium on Combating Wildlife Crime (ICCWC), which helps enforcement agencies prevent and detect illegal logging and other forest offenses as well as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), with around 2,000 delegates representing more than 150 governments, indigenous peoples, non-governmental organizations and businesses. Other regional partnerships, such as the recent one between Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, have been put in place to improve customs at borders and ports and bolster enforcement.

Smaller efforts are working to make big changes, too. Rainforest Connection, a San Francisco-based non-profit (check out the Kickstarter campaign here) converts old phones and parts of old solar panels into devices to detect illegal logging and poaching. The recycled devices pick up real-time sound of chainsaws and notify conservationists, who can then put a stop to the damage before it continues. But even with these efforts, both big and small, illegal logging continues at an alarming rate.

The only effective way to combat illegal logging is global collaboration. It will take more effectively monitored trade methods, harsher punishments, and smaller-scale efforts, such as consumer awareness campaigns, to hinder the exploitation of our natural resources. The U.N. says the three most important law enforcement efforts would be to “reduce profits in illegal logging,” “increase the probability of apprehending and convicting criminals at all levels involved including international networks,” and “reduce the attractiveness of investing in any part of production involving high proportions of wood with illegal origin.” But, like we’ve discussed before, it’s not just the people in charge that matter. Everyone – government, corporations, investors, and consumers – will all have to play a part in reducing the viability of the illegal timber trade.

Though it’s difficult for consumers to determine where their paper towels or kitchen cabinetry actually came from, it’s a good idea to look for products certified by the Forest Stewardship Council. The certification means the wood was sourced in compliance with local laws and with respect for the rights of indigenous peoples. It’s not fool-proof but it’s a start. And ask your go-to stores to carry FSC-certified paper goods and other wood products.

Illegal logging will not cease completely soon. “Until the legal system shifts the focus away from transit documents and toward verifying extraction of wood at the source and the subsequent chain of custody,” Finer says, “widespread illegal logging will likely persist.” The problem is too big. But with more initiatives, tougher penalties, and stronger global collaboration, the social, environmental, and economic effects of illegal logging may slowly and steadily decline over time.