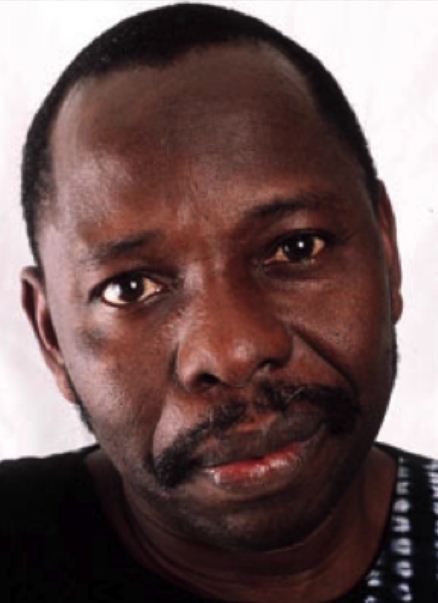

Ken Wiwa, the son of human rights activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, says in this article published in The Guardian of London, that Nigeria’s Ogoniland still looks as devastated by oil pollution as when the junta executed his father 20 years ago. But, according to him, the carbon economy seems to be reaching a tipping point at last. Wiwa was a Nigerian government adviser from 2006 to 2015

Twenty years ago today my father and eight other Ogoni men were woken from their sleep and hanged in a prison yard in southern Nigeria. When the news filtered out, shock and outrage reverberated around the world, and everyone from the Queen to Bill Clinton and Nelson Mandela condemned the executions.

What I recall of the long days and sleepless nights afterwards was the slogan that caught on with my father’s devastated friends and supporters; we were united in a determination to ensure that “his death must not be in vain”. So has anything changed?

Nigerian government finally sets up fund to clean up Ogoniland oil spills

The trite answer is yes and no. Back in 1994 Ken Saro-Wiwa and scores of Ogoni men were arrested, detained without charge for six months, tortured and denied access to lawyers, doctors and family. When they were finally brought to court, they were arraigned before a military tribunal and accused of murder.

That it was a kangaroo court is no longer in dispute. The trial and execution were consistent with the way Nigeria’s military regimes summarily dealt with people they regarded as a threat to their authority. A UN fact-finding mission led by eminent jurists vigorously condemned the process, and John Major, Britain’s prime minister, described the trial as “fraudulent”, the convictions as a “bad verdict”, and the executions as “judicial murder”.

Despite several aborted attempts to reconcile the victims and perpetrators, my father and the other men remain convicted criminals in Nigeria’s legal books. More worrying is that, although the military junta that killed my father is long gone, Nigeria’s civilian government has yet to come to terms with a man and a community whose story stands as enduring testimony to the consequences of reckless and unaccountable oil production.

My father went to the gallows an innocent man. He loved his country but refused to remain silent while his land and his people were being exploited. His real “crime” was in exposing the double standards of Shell, who had been quietly drilling oil for years in Nigeria, earning good profits for its shareholders but leaving the host community wallowing in levels of pollution that he described unflinchingly as “devastation”, pointing out that the operations in Ogoniland betrayed Shell’s own global standards.

If my father were alive today he would be dismayed that Ogoniland still looks like the devastated region that spurred him to action. There is little evidence to show that it sits on one of the world’s richest deposits of oil and gas.

And yet the impression that nothing has changed is deceptive. For a start the Ogoni’s claims of pollution against Shell have been vindicated. Shell always bristled against my father’s accusations, insisting, without any apparent sense of irony, that he was being emotive.

In 2006, however, the Nigerian government invited the United Nations Environment Programme (Unep) to assess the in Ogoniland and the Niger delta. Among its sobering findings was the conclusion that . Although the report was not comprehensive, it represents the most detailed and evidence-based analysis of the situation in Ogoni. In one community, researchers reported that surface water contained 900 times acceptable levels of cancer-causing benzene. Unep even recommends that Nigeria establish a community cancer registry.

Although the Unep report was delivered in August 2011, the implementation of its recommendations is proving to be a political, fiscal, legal and administrative challenge to the government. I can attest that, despite its skittish hypersensitivity to criticism of its Ogoniland operations, Shell has repeatedly told me it is (£650m) that Unep recommended to kickstart the cleanup. However, my community is still waiting for social justice, with gathering impatience.

Only time will tell whether this process will deliver. Nigeria has plenty of challenges beyond Ogoniland. Many of these arise because our leaders lack the courage to right the wrongs of the past. While we are busy applying plasters to fundamental malfunctions, these efforts could be superseded by seismic shifts in law, in technology and in public opinion.

In the past 10 years the Ogoni have registered landmark victories in court cases against Shell in New York and . I am sure my father will be looking down and chuckling that activists who cut their teeth on the Ogoni case were part of the coalition that last week pushed President Obama to reject the controversial Canada-to-Texas Keystone XL pipeline. At the same time Exxon is facing the possibility of legal action over claims that it lied about climate change risks, which Exxon denies. We may finally be arriving at a tipping point in the carbon economy, and perhaps one day my father’s story will be more than a footnote in that history.

Sometimes it seems as if 10 November 1995 was another era. In some ways it was, and in others it feels like it was just yesterday. Between the disabling nature of his death and the enabling tests of time, one thought still sustains me: it is the old idea that the arc of the moral universe may be long, but it still bends towards justice.