Unless you have total disregard for nature or you’re one of the people who value wildlife (both animals and plants in the wild) only in terms of exploitation for timber, game and other non-timber forest products, then you must be commending Ghana for its protected wildlife areas. They remain what are left of the country’s pristine ecological areas that promote biological diversity and thereby contribute to human survival.

Of the country’s 21 wildlife protected areas, there are seven designated National Parks, six Resource Reserves, two Wildlife Sanctuaries, one Strict Nature Reserve and five Coastal Wetlands of International Importance also known as Ramsar sites, most of which have unfortunately been massively exploited for other uses.

Mole National Park is the largest covering an area of 4,577km². Due to its rich animal, birdlife and plant diversity, the area was set aside as wildlife refuge in 1958, and designated as a National Park in 1971 (along with other areas) under the Wildlife Reserves Regulations, 1971.

As is common to all of such protected areas, Mole National Park provides protection for species from hunting and poaching, among other things. It serves to secure the area’s uniqueness as a naturally occurring refuge island to preserve endangered species in particular and to offer recreational opportunities.

The Park is mainly located near Damongo in Ghana’s Northern Region and extends a little bit to the Upper West Region, stretching across five administrative districts. They are West Gonja, Sawla Tuna Kalba, Wa East, North Gonja and Mamprusi Moaduri Districts. It is 146km south west of Tamale the Northern Regional Capital and 25km from Damongo the Capital of West Gonja District.

Genesis of the Mole National Park

The beginnings of the Mole National Park can be traced to the establishment in 1933 of the Tsetse fly Control Unit of the Ministry of Agriculture for the eradication of the tsetse fly menace that was ravaging large animals both wild and domesticated, and continued to do so for about 20 years. The programme was also to prepare the grounds for large scale cattle ranching. During 1949 to 52 the colonial administration appointed Game Wardens to facilitate gaming in the country. Then in 1957, President Kwame Nkrumah appointed A.R. Charleswick as Game Warden to manage the area that eventually became a Wildlife Sanctuary.

Architects of the Park

There is no doubt that the wildlife officials then known as Game Officers – late Dr. Asibey, Punguse, late Ankunde, Ofori Frempong, Naa Nuhu, Ben Volta, and the host of others including some foreign nationals, who were instrumental in firming up the Park’s establishment did so out of genuine interest and concern for the general welfare of the nation. They looked past the immediate benefits of unchecked hunting and farming, to the long term goals of management for ecosystem protection and eventually for food security and sustainable development.

These people were self-motivated and passionate, because they understood the linkage between a healthy and well-functioning wildlife ecosystem and a vibrant human life and sustainable development. They understood that the term “wildlife,” does only refer to wild animals, but also encompasses all undomesticated life forms including birds, insects, plants, fungi and even microscopic organisms.

They appreciated that for maintaining a healthy ecological balance on this earth, animals, plants and marine species are as important as humans. That the eco-system is all about relationships between different organisms connected through food webs and food chains. So if just one wildlife species gets extinct from the eco-system, it is likely to disturb the whole food chain ultimately leading to disastrous results. For instance, the bee is vital for growth of certain crops as a result of their pollen carrying roles. So, if the population of bees diminishes because of destruction of all types of forests, the growth of food crops will definitely suffer for lack of pollination.

The architects were people who cared more about the welfare of wildlife animals and their habitat, than about their own lives. They formed the early staff of the then Game Department (now Wildlife Division of the Forestry Commission) and set the pace for the management of Mole National Park and indeed all the other protected areas, based on selfless commitment to duty.

Management of the Park

For proper management, the park is partitioned into four management areas called ranges. They are known as Headquarters, Bawena, Jang and Ducie Ranges. These are sub-divided into beats for effective law enforcement and ground coverage. Each range has at least twenty staff pooled into a range camp and deployed regularly on patrol in the beats to check poaching, unauthorized entry and other illegal activities. There are staff and satellite camps within the ranges used as rest stops and focal points during patrols.

Staffers also gather biological data and all are fed into a computerised Management Information System (MIST). According to Ali Mahama, the Law Enforcement Officer at Mole, “the MIST is used to monitor patrolling effort and effectiveness as well as monitor wildlife distribution and trends.” He explained that the overall objective is to improve Park management and maintain the integrity of the Park.

The Perfect Tourist Destination

The Park admits visitors from all over the world for game viewing, camping, hiking, research and education. Visitors to the Park have gradually increased from a total of 2,322 recorded visitors in 1989 to 17,758 recorded 2017. As at the first quarter of 2018 a total of 5,226 people had visited the Park. The visitors are made up of domestic tourists including adults, students of tertiary and secondary institutions. Others are foreign adults, nature lovers, bird watchers, students and children. Apart from the bogs, duikers, bushbucks, warthogs and baboons, one might also be lucky to watch a team of elephants cooling themselves by smearing mud on their skins or doing their “beauty treatment.”

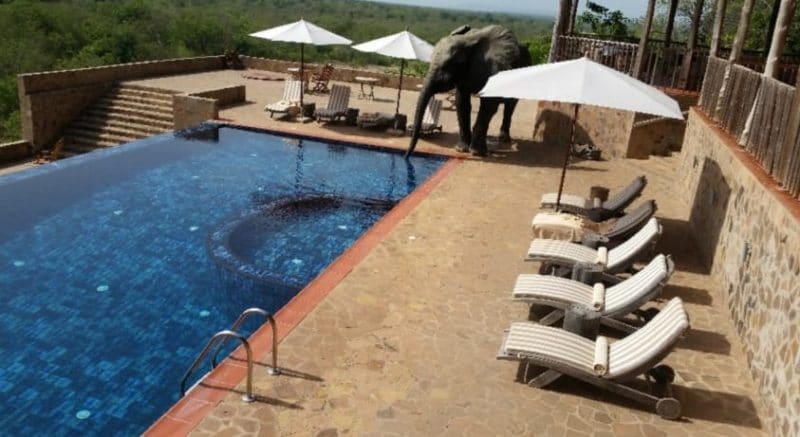

But you could even get a pleasant surprise from the now known young male elephant, who according to the Manager of Zaina lodge, Andrew Joseph Murphy, “visits the lodge once a year to cool itself with water from the swimming pool at the Lodge.”

Mole also has a historical legacy and Oral tradition says the park has links to the national slave trade route. The ancient caravan route from Salaga to Wa and beyond to Mali, passed through the heart of the park. This route was used for both trading and to transport slaves to coastal markets. The park Headquarters is located right at a place where Samore and Babatu, the two famous slave raiders raided and erased a village to the ground. The Headquarters is named after Samore. There is also a cave in the Konkori escarpment that was used as a refuge from slave raiders by the local people.

The upgrading of the existing boarding facilitates as well as the construction of an eco-lodge facility have helped to revive tourism to Mole following the Ebola scare that caused the numbers to drop in 2013 and 2014.

Contribution to GDP

It is obvious that Mole National Park is a significant contributor to the over 1.3 billion USD, which is a direct contribution of the tourism sector to annual revenue generation representing about 2.8% GDP.

Current threats to Mole’s existence

While, staffers have been able to keep illegal hunting and poaching to the minimal levels, poachers continue to threaten their lives. A number of staffers have lost their lives over the years, with the latest occurring in March 2018, when the leader of a patrol team was hit and killed by poachers.

Such attacks, coupled with inadequate funding and logistics for the sector, have begun to wear out the morale of staffers. Nevertheless, their passion to keep Mole as intact as possible remains key, even in the current fight against illegal logging of Rosewood. The species is one of the dominant trees in the Park and provides food for most of the mammals. Bees love the nectar from the Rosewood flowers that provide the main ingredient for honey in the area. Indeed, fringe communities such as Mognori and Murugu are now famed for producing the best honey in Ghana.

However, the unprecedented illegal logging of Rosewood is threatening not just the Park’s existence, but the local honey industry and the functionality of the Community Resource Management Areas (CREMAs).

Staff Response

Staffers of Mole have responded by cutting up and burning Rosewood logs felled in the Park as well impounded equipment and vehicles. The Park Manager Farouk says, “Though this measure has drawn sharp criticisms from some quarters, it has helped to curtail the menace in the Park for now.” He emphasised that “Mole was created by the passion of our seniors and with our passion we will sustain the Park against all odds.”

By Ama Kudom-Agyemang