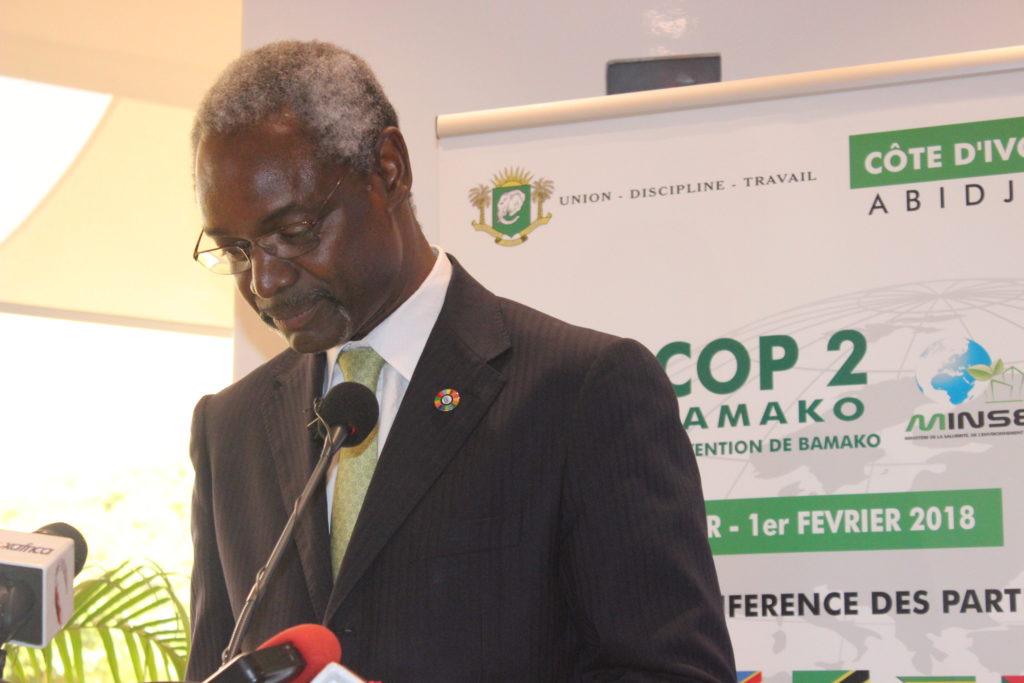

Ibrahim Thiaw, UN Under Secretary General and Executive Secretary to the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) in a reaction to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report on Climate Change and Land released on Thursday, August 8, 2019, says that the world can’t head off the worst ravages of climate change without action on land degradation

We have known for over 25 years that poor land use and management are major drivers of climate change but have never mustered the political will to act. With the release of the IPCC special report on climate change and land, which makes the consequences of inaction crystal clear, we have no excuse for further delay.

We cannot head off the worst ravages of climate change without action on land degradation. The knowledge and technologies to manage our lands sustainably already exist. All we need is the will to use them to draw down carbon from the atmosphere, protect vital ecosystems and meet the challenge of feeding a growing global population. We must harness the enormous positive potential of our lands and make them part of the climate solution.

With the help of our scientists, I will ensure the issues in this report that are within the scope of the Convention are presented to ministers for strong and decisive action when they meet at the world’s largest intergovernmental forum where decisions on land use and management are made, the 14th session of the Conference of the Parties to the UNCCD, taking place in New Delhi, India, in three weeks’ time.

The IPCC report is one of four major assessments released over the last two years that show the wide-ranging impacts of land degradation. It is not just the climate that suffers when land quality declines. Land degradation jeopardizes our ability to feed the word, threatens the survival of over a million species, destroys ecosystems and drives resource-related conflicts that demand costly international interventions.

These problems are no longer local problems. The report underlines that the increasingly global flows of consumption and production means that what we eat in one country can impact land in another. In the wake of land degradation and drought, communities are breaking down due to the swift and devastating loss of life and livelihoods.

Faced with these life-changing consequences, the UNCCD has developed a robust policy framework that can enable countries to avoid further land degradation and recover land that has become virtually unusable.

Change is happening, but not fast enough. In the last four years, 122 of the 169 countries affected by desertification, land degradation or drought have embarked on setting national targets to halt future degradation and rehabilitate degrading land to ensure the amount of healthy and productive land available in 2015 does not decline by 2030 and beyond.

Last year, these countries submitted baseline date to verify this achievement. And in just three years, close to 70 countries have set up national drought management plans to reduce community and ecosystem vulnerability to droughts, which the IPCC says will become stronger, more frequent and more widespread.

This shows that commitment to reversing land degradation is growing, even though much work remains. More than two billion hectares of land are degraded. Initiatives to restore land on a national or landscape level are not only vital in reversing the process. They are critical for helping the global community mitigate and adapt to climate change in the short term, using soil and vegetations through methods that do not harm the Earth.

When the ministers meet in September, I

expect the IPCC report to have a strong influence not only on the policy

decisions they will debate, but the will to take them home for appropriate action.

Science can help politicians develop informed policies that will support

ordinary people to prepare, act and create more positive pathways to the

future.