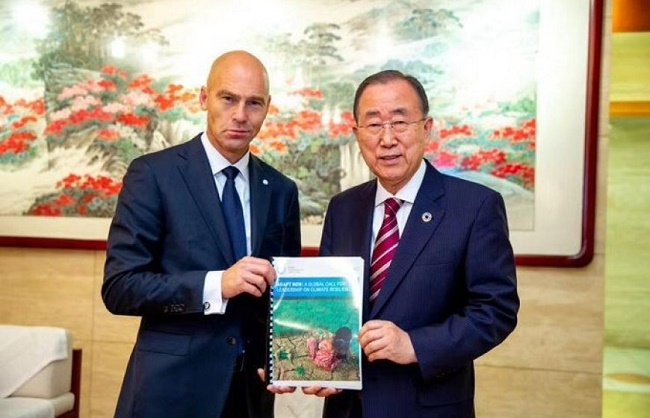

With top scientists warning that Africa is paying an intolerable price for the impacts of climate change, it’s time for the rich world to honour its pledges on climate finance and investment, write Ban Ki-moon, 8th Secretary-General of the United Nations, and Patrick Verkooijen, CEO of the Global Centre on Adaptation

The latest report from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) came with all the usual warnings of the calamities that will befall us if we do not stop global warming now.

But this is hardly news in Africa, where people are already living with some of the worst effects of climate change – a problem they did not cause and are powerless to stop.

It is the rich world’s accumulated greenhouse gas emissions that are inflicting devastating droughts or torrential floods across vast swathes of the continent. It is here where hunger is on the rise and decades of economic and social progress have been thrown into reverse. Worse, African countries are having to borrow more, and get deeper into debt, to recover after climate disasters. How is this fair?

Too little, too late

The IPCC report puts climate justice into sharp focus. It says: “Prioritising equity, climate justice, social justice, inclusion and just transition processes can enable adaptation and ambitious mitigation actions and climate-resilient development.”

But, as yet, we have no mechanism to bring about climate justice. The COP27 climate conference in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, last year agreed to set up a “loss and damage fund” to compensate poor countries for the harm caused by climate change.

So far that fund is empty. The expectation is that it will attract some pledges by the time the next U.N. climate summit convenes in the UAE later this year, but we are not holding our breath.

International finance for reducing emissions and adapting to climate risks in the developing world has repeatedly fallen far short of the $100 billion annual target set by donors, including the United States, Japan and European Union, 14 years ago. The trickle of money that arrives is tied up in red tape.

That is why vulnerable countries are having to borrow to pay for the increasing costs of climate catastrophes.

Last year’s heavy monsoon rains caused more than $30 billion of damage and financial losses in Pakistan, nearly 9 percent of the country’s GDP. When a country is small, climate losses can exceed its entire economic output. In Dominica, for example, storm damage from Hurricane Maria in 2017 cost the country more than twice its annual GDP.

African countries face seeing their GDP growth rate fall by up to 64% by the end of the century, even if the world succeeds in limiting global heating to 1.5C. The economic cost of climate disasters in developing countries is projected to reach as much as $580 billion a year by 2030.

In 2021, more than 30 million people were displaced by climate-related disasters. In Africa, 52 million people – 4 percent of the population – have suffered either drought or floods over the past two years, according to the latest State and Trends in Adaptation in Africa 2022 report. A drought in the Horn of Africa, now in its fourth year, is worse than the conditions that led to famine in 2011. Close to 23 million people are currently highly food insecure in Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia.

How does the world expect countries to protect vulnerable populations if the international funds promised are not there?

Investing for a more resilient future

Africa does not want aid or emergency relief funds. It wants to invest in a climate-resilient future. It needs funding to rebuild roads, bridges and buildings so they can withstand frequent flooding and storms. It needs to invest in R&D to develop new crop strains that can withstand prolonged droughts. It needs to give farmers access to climate data services, and much else besides.

Climate adaptation needs to be built in so that communities not only build back after a natural disaster, but also build back better.

The key is to be able to do this quickly and at scale, because right now the world’s poorest and most climate-vulnerable nations are at risk of falling into a destructive debt and climate-disaster trap.

Africa has a plan on how to do this – the Africa Adaptation Acceleration Programme is an Africa-owned and Africa-led initiative developed by the Global Centre on Adaptation (GCA) and the African Development Bank (AfDB) in close collaboration with the African Union. It serves as the implementation of the Africa Adaptation Initiative (AAI) to mobilise $25 billion to implement, scale and accelerate climate adaptation across Africa. Since 2021, AAAP has mainstreamed climate adaptation in over $5.2 billion of investments in 19 countries.

Restoring Trust

Africa put its faith in the Paris Agreement on climate change but has been shortchanged. It is time for industrialized countries to make good on their broken promises and fully fund the need for climate adaptation and mitigation in developing countries.

Doing so will not only restore the fractured trust between climate-vulnerable regions and the rich world; it will also be the surest way to achieve climate justice and build a more stable global order.