The hole in the Antarctic ozone layer is beginning to close, scientists have discovered.

Researchers from the University of Leeds and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the US, have confirmed the first signs of an increase of ozone, which shields life on Earth from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays.

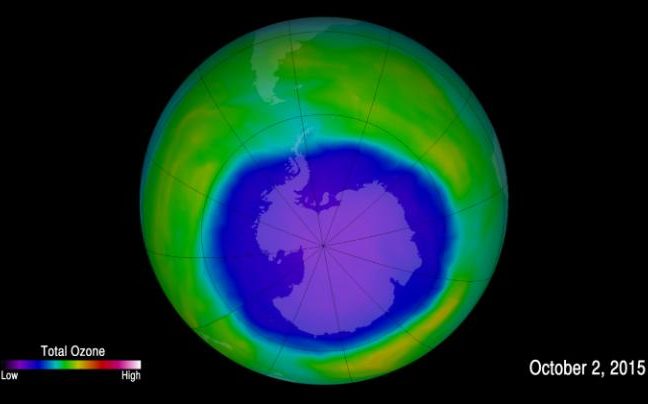

New findings, published on Thursday in the journal Science, show that the average size of the ozone hole each September has shrunk by more than 1.7 million square miles since 2000 – about 18 times the area of the United Kingdom.

They now predict that the hole above the South Pole will close permanently by 2050.

The improvement is down to the success of the 1987 Montreal Protocol – which banned the use of chlorofluorocarbons in aerosols and fridges.

“Observations and computer models agree; healing of the Antarctic ozone has begun,” said Dr Ryan Neely, a Lecturer in Observational Atmospheric Science at Leeds.

The ozone hole was first discovered using ground-based data that began in the 1950s and in the mid-1980s, scientists from the British Antarctic survey noticed that the October total ozone was dropping.

The hole has continued to widen ever since, peaking in 2000 at 15 million square miles and remaining fairly constant over the past 15 years, except for a few spikes.

However new modelling by the team showed that most recent spikes in ozone depletion were caused by volcanic eruptions rather than chlorine in the atmosphere and the hole is actually closing.

Professor Susan Solomon of MIT who led the research added: “We can now be confident that the things we’ve done have put the planet on a path to heal.

“We decided collectively, as a world, ‘Let’s get rid of these molecules’. We got rid of them, and now we’re seeing the planet respond.”

The ozone hole begins growing each year when the sun returns to the South Polar cap from August, and reaches its peak in October.

Co-author Dr Anja Schmidt, an Academic Research Fellow in Volcanic Impacts, said: “The Montreal Protocol is a true success story that provided a solution to a global environmental issue.”

By Sarah Knapton (Science Editor, The Telegraph)