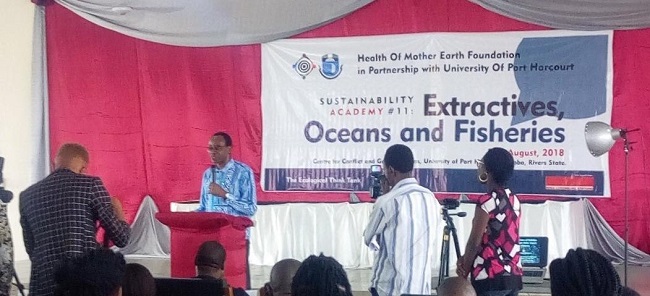

Nnimmo Bassey, Director of the ecological think tank, Health of Mother Earth Foundation (HOMEF), speaking at the Sustainability Academy (with the theme “Extractives, Oceans and Fisheries”) on Friday, August 31, 2018 at the Centre for Conflict and Gender Studies, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria, laments the spate at which oceans are being polluted

It has become common knowledge that by 2050 there will be more plastic in the oceans than fish. That is quite alarming. More alarming, however, should be the fact that we are already consuming a lot of plastic through the fish that still swim in our waters. Besides health impacts, the economy of fishers and their dependents is receiving crushing blows from this trend as our oceans literally get turned into dumpsites.

The oceans present pictures of limitless resources begging to be dragged out into the markets and kitchens of this world. This sense of the ocean as an inexhaustible storehouse has empowered some unscrupulous persons to throw caution to the winds as they trawl the seas, oceans and lakes catching everything from the fingerlings to mature fish. Sadly, some of these rogue fishers do not respect national boundaries and behave no better than sea bandits.

Besides the stealing of sea resources, there is the alarming harvesting of fish on the West African coastline for the production of fish meal for use in industrial aquaculture production in Europe and Asia. This harvesting of fish for fish meal has raised the price of fish beyond the reach of the people who depend on them as a key source protein.

The oceans and our lakes have also become zones of interest for the extractive industries – miners and oil companies. Their activities present special dangers to the health of our creeks, rivers, lakes and oceans. The efforts to keep up profits has triggered a rush to mine the seabed in ways that should attract serious attention.

Dead Whales, Red Flags

Our coast lines are dotted with oil rigs, oil platforms and armadas of seismic vessels. Lakes Chad, Albert, Victoria, Kivu, Tanganyika, Malawi and Turkana have all attracted the claws of the oil and gas industry. These activities if not checked portend grave dangers for national security and, more urgently, for fishers and the health of our peoples.

The epidemic of dead whales washing onshore is just one indicator that all is not well. In recent months we have had reports of dead whales off the coasts of South Africa, Nigeria, Australia, Ireland, Germany and the United States of America, to mention just a few. In the case of the eight Cuvier’s beaked whales that washed up on the west coast of Ireland, scientists believe that they died of impacts of British military sonar. Of course, the British Navy denied any link between their maneuvers and the dead whales. However, naval sonars are known to have deadly impacts on whales.

Some navies use these low frequency active sonar (LFA) systems in scouring the sea bed for obstructions, mines and other elements. They use a number of underwater speakers to pulse low-frequency sounds at about 215 decibels for roughly 60 seconds a pop. The sounds travel over hundreds of kilometres and can interrupt the lives and activities of marine mammals, breaking up their communications, causing disorientation and other problems. These sonars are found in approximately 70 per cent of the world’s oceans.

The seismic exploratory activities of oil, gas and mining companies are carried out using techniques that are comparable to the naval sonars. These seismic surveys use sound energy (at decibels higher than levels that normally occur in the oceans) to map geological structures deep beneath the seabed.

Some apologists of the extractive sector continue to argue that having dead sea mammals wash up onshore is normal and is to be expected. What they do not say is that the carcasses that we see are only of those that washed to inhabited shorelines. How many dead whales and other large aquatic species die and are buried in the deep or are simply out of sight?

Threats to Our Common Heritage

In a recent letter to the International Seabed Authority (ISA), global citizens demanded that the seabed should be off limits to mining. They stated, “Moreover, a global public knowledge that deep sea extraction is under discussion is still extremely limited, as is public understanding of the implications of such a move. As deep-sea mining would impact the common heritage of (human)kind in ways that are not yet scientifically well-understood, time should be taken to initiate a wider public discussion and to carry out additional scientific research.”

The letter further stated, “The common heritage of (human)kind is a significant equity principle in international law. This principle was formally applied to the deep seabed through a 1970 UN resolution declaring that the ocean floor in international waters – called the ‘Area’ in international law – be employed for peaceful purposes.” It added that, “It is our view that this must not proceed without a more transparent and thorough global assessment of the ecological risks associated with deep-sea mining, as well as a more rigorous consideration of a benefit-sharing mechanism via which the common heritage principle will be upheld.”

Water Grab Through Pollution

Water pollution from oil spills and mine tailings are sources for great concern about the quality of our waters and the overall health of the marine ecosystem. The same can be said of factories and industrial installations along our coastlines, including oil refineries that use the ocean as their rubbish dump, pumping toxic loads into them and deeply compromising the health of the aquatic lives in the process.

Researchers believe that by 2035 some 40 per cent of the world population will live in areas having water scarcity. It is also said that industries account for a fifth of global water use compared with 5 per cent for humans while agriculture uses the rest. We believe that industry uses much more water than estimated because these estimates do not include the waters that industry have polluted and rendered useless for other purposes.

The creeks, rivers and swamps of the Niger delta, for example, have all be privatised by the oil companies through pollution. Our continental shelf and deep waters have been partitioned and are effectively owned by the oil companies because of the security zone (often up to 5 km radius) around their installations that are cordoned and closed to fishers, including areas with endemic fish species. So, our waters are also privatised through security cordons for unhindered extractive activities. This is a clearly objectionable privatising of the commons.

Fishers Unite!

The double jeopardy for our fishers is that with polluted coastlines, the option they have to secure good catches is to go into the deep offshore, but most of them do not have boats that can venture far off the coastlines. This is the tragic economic predicament of our fishers: disrupted by pollution, stopped by the military and blocked by economics. These will remain and self-reinforce until, and unless, fishers unite and declare that fish is more valuable than oil, coal or gold. The FishNet Alliance presents a strong platform to push for water bodies devoid of extractives.

It is time to challenge activities to pose danger to our marine resources. Citizens can win when we stand together and build webs of resistance. Resolute activists in New Zealand just won an inspiring case rejecting the mining of 50 million tonnes of ironsand from a 66 square kilometres area off the South Taranaki Bight that was to be done over a period of 35 years. More victories are possible.