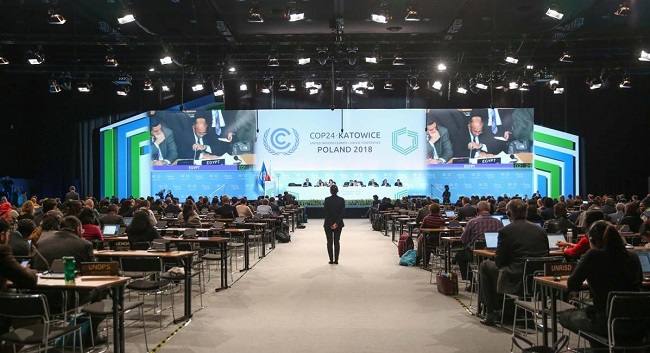

The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), in an analysis of the the 24th Session of the Conference of the Parties (COP24) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that held from December 2 to 14 in Katowice, Poland, examines the rulebook by focusing on key parameters of success, such as: resolution of contentious political issues; delivering effective guidelines for a dynamic architecture; and building the basis for increased ambition

“From now on it is only through a conscious choice and through a deliberate policy that humanity can survive.” – Pope John Paul II

In a world facing the increasingly devastating impacts of climate change, the Katowice Conference was a pivotal moment. With the deadline to finalise the Paris Agreement “rulebook” looming, parties needed to overcome long-standing disagreements and hammer out the technical details of a robust and ambitious post-2020 climate regime.

But much has changed in the three years since Paris. Despite the clear warnings of science and the steady drumbeat of extreme weather events worldwide, global emissions increased in 2017. The political context has shifted, with a marked turn away from multilateralism to populism and, in some cases, opposition to scientific evidence. The transition to a zero-emissions economy is not yet fully underway, a fact made clear by the location of the Katowice Climate Conference in the heart of Poland’s coal-producing region.

Despite these political headwinds, the long-standing disagreements among countries, and the technical complexity of the task, COP 24 delivered. The “Katowice Climate Package” adopted late on Saturday, December 15, 2018 puts in place a set of implementation guidelines that were considered by many to be sufficiently robust. But does it establish the strong and stable institutional framework needed to implement the Paris Agreement? And, given the signals of increasing urgency, what does this framework mean for ambition in the post-2020 era? This brief analysis will examine the rulebook in more detail by focusing on key parameters of success, namely: resolution of contentious political issues; delivering effective guidelines for a dynamic architecture; and building the basis for increased ambition.

The Road to the Rulebook

COP 24 had one clear goal: to deliver the “rulebook.” After three years of difficult negotiations, parties had two final weeks to turn the Paris Agreement’s broad commitments into the detailed technical guidance needed to measure mitigation, account for finance, and ensure transparency. Since establishing this deadline at COP 22 in Marrakesh, countries had barely budged from their negotiating positions. And despite an extra negotiating session in Bangkok in September 2018, delegates arrived in Katowice with fundamental differences yet to be resolved in a 236-page text.

These differences were both long-standing – rooted in historical debates about responsibility and leadership – and specific to differing interpretations of the Paris Agreement itself. The primary sticking point was differentiation. Developing countries have long argued that they should be granted flexibility in their mitigation efforts, while developed countries have sought common rules that will hold all, especially emerging economies, equally accountable. The Paris Agreement provided little clarity on this issue. While it broke the binary division between Annex I and non-Annex I parties, it replaced this with language that is either ambiguous or varies across different provisions. For example, in financing provisions, the Paris Agreement introduced the concept of “other parties” that are encouraged to provide voluntary support. Establishing a “robust” rulebook therefore required resolving these ambiguities in a way that balances developing countries’ differing capacities with clear and common guidance that ensures higher ambition.

Additionally, parties had to overcome simmering distrust about the sufficiency and predictability of financial support to developing countries, which they regard as crucial to enhance their ambition. In the past year, this distrust had crystallised in debates over “Article 9.5” (indicative information on provision of finance) and the process to establish a new long-term finance goal. As negotiations proceeded slowly during the first week, and chaotically behind closed doors during the second, some expressed fear that the divides over differentiation and finance would simply be too broad to bridge, and that another Copenhagen catastrophe could be in the making.

Parties delivered despite these fears. But how strong is the Katowice Climate Package? The rulebook could be expected to deliver stronger ambition in at least four ways. First, by resolving politically difficult issues left lingering from Paris. Second, by balancing the need for binding and prescriptive guidance with the need for flexibility, to maximise both effectiveness and participation by all countries. Third, by enabling a dynamic agreement through strong collective and individual review mechanisms and timelines for revisiting its guidelines. And fourth, by addressing all relevant issues now, as opposed to leaving them for future negotiations.

A Balanced Rulebook

Resolving long-standing issues was a prerequisite for a successful outcome, as parties would only agree to what they perceived to be a balanced package. The ministerial negotiations during the second week were crucial for unlocking the agreement on the two most contentious issues: differentiation and finance. In the final agreement, more uniform and mitigation-centric NDC guidance, which developed countries see as central to the Agreement, is balanced with improved processes for financial support for developing countries.

In guidance for communicating and accounting for mitigation targets, the majority view of creating a common set of elements that each country would apply based on the type of its NDC – an absolute emission reduction target or a relative emission intensity target, for example – prevailed over long-standing calls for a binary set of rules, one for developed and another for developing countries, which had been supported by the Like-minded Developing Countries and Arab Group. These groups also called for a “full scope” approach to guidance on NDCs, by which countries would communicate their mitigation intentions together with their plans on adaptation and means of implementation. The agreed guidance focuses on mitigation but, in an acknowledgement to these countries, allows for inclusion in NDCs of information on adaptation and on mitigation co-benefits resulting from adaptation actions or economic diversification plans.

Developing countries’ calls for a clear process to assess and review developed countries’ indicative finance provision reports were heeded. The agreed guidance in this area (Paris Agreement Article 9.5) now provides for synthesis reports, workshops, and ministerial meetings that will focus on evaluating finance information and, undoubtedly, its sufficiency.

Developing countries also welcomed an agreement to initiate, in 2020, deliberations on setting the new collective quantified finance goal for the post-2025 period. Under the Paris Outcome, countries agreed to set this goal, but developed countries had so far demonstrated unwillingness to even set a date for starting discussions. While the rationale for this position was not openly spelled out, many attributed this initial reluctance to discuss the new finance goal to the US walking away from the Agreement as well as political and economic challenges in many industrialised countries.

Also significant for developing countries was the final decision on the Adaptation Fund, as many of these countries consider adaptation finance a top priority. The Adaptation Fund, which currently serves the Kyoto Protocol and receives shares of proceeds from its offsetting mechanisms, will now exclusively serve the Paris Agreement once the share of proceeds from the Paris Agreement offsetting mechanism becomes available. The Fund will also be financed by voluntary public and private sources.

An Effective Rulebook

Reaching compromise on the politically-challenging issues of differentiation and finance enabled parties to focus on developing guidance that would be binding and detailed enough while maximising participation. Many did not expect countries to reach an outcome that contains both legally-binding language, such as “shall” or “should,” and prescriptive guidance that ensures information communicated by countries is clear and comparable. However, the overall sense was that the 97 pages of operational guidelines delivered by parties in Katowice represent a commendable outcome in both regards.

The transparency framework, which, together with the global stocktake, is often considered to be the core component of the Paris Agreement’s “ambition mechanism,” delivers on all these parameters: the detailed guidance on countries’ reporting and review obligations establishes that all parties “shall” submit transparency reports every two years. The transparency guidelines include elements that are common for all parties, including common reporting tables and a requirement to submit the first report by 2024, but they also allow for flexibility for developing countries in the scope, frequency, and level of detail of reporting. However, developing countries are also required to explain why they need the flexibility and provide self-determined time frames to improve reporting. In many areas of the rulebook, including transparency, the guidelines also give the most vulnerable countries, namely LDCs and SIDS, added flexibility in terms of how and when they apply the guidance.

It was also crucial that the guidance emerging from Katowice enable the Paris Agreement to become the dynamic ambition mechanism it was intended to be, with comprehensive rules for five-year cycles for submitting national plans, or NDCs, and reviewing their implementation, on the one hand, and a robust system for taking stock of collective progress, on the other. The global stocktake, which is the central mechanism for this latter purpose, was duly operationalised, but left some discouraged. Many observers from the environmental NGO and research community, as well as many developing countries, felt that there is insufficient guidance on how to consider equity in the inputs and outputs of the stocktake. Observers also lamented what they felt was a near-exclusion of non-party stakeholders from the process, with their role reduced to making submissions and not, for example, participating in the consideration of outputs from the stocktake. Some fear that without accounting for equity or engaging non-party stakeholders, the global stocktake could be less effective in holding countries accountable and in presenting a sufficiently comprehensive overview of global efforts.

The guidelines from Katowice also give some teeth to the implementation and compliance committee, which, as set in Paris, has a facilitative role only, but is now empowered to initiate, of its own accord, consideration of non-compliance in certain cases. These include when a country has not communicated or maintained an NDC, submitted its transparency report, or, in the case of a developed country, its indicative finance report.

A further dimension of the rulebook’s contribution to dynamism is how it mandates adjustments to the rules over time. Many sections of the Katowice package set timeframes for review and possible revision of the guidance. One such example is the guidance on information and accounting related to mitigation, which is mandated to happen in 2028, even if some groups, such as AOSIS, felt that this will come too late.

Finally, one of the most important accomplishments of the Katowice outcome is that parties were able to agree to most elements of the Paris Agreement Work Programme. Failing to agree would have weakened external perceptions of countries’ determination to implement the Agreement and damaged the credibility of the UNFCCC process. The only major exception was cooperative approaches under Article 6 relating to guidance for international transfers of mitigation outcomes, rules for the Agreement’s carbon offsetting mechanism, and a work programme for non-market-based approaches. Decisions on all these items were postponed to the next CMA session in 2019 due to what many described as one country’s opposition to strict rules on double counting of emission reductions. This refusal caused negotiations to stretch late into Saturday as countries sought to save the work accomplished during this session and to agree to key rules and institutional arrangements, which they felt were important to provide a signal of continuity to markets and the private sector.

Parties’ inability to resolve the future role of markets in the institutional architecture of the Paris Agreement at COP 24 did not necessarily weaken the outcome but will need to be quickly resolved.

A Rulebook that Enables Ambition

The “1,000 little steps countries took together” to reach agreement on the rulebook adopted in Katowice will undoubtedly help “move us one step further to realising the ambition enshrined in the Paris Agreement,” as noted by COP 24 President Michał Kurtyka upon gaveling the package through. The rulebook itself sends an important political message that the Paris Agreement is alive and well. But what does it mean for more ambitious climate action going forward?

Many who came to Poland expected further political signals on ambition, in the form of a strong outcome, or perhaps even a continuation of the Talanoa Dialogue, broadly considered as a “pre-global stocktake” of sorts, initiated by the Fijian COP 23 Presidency and based on a Pacific storytelling tradition. There were also calls for decision text encouraging countries to enhance their NDCs by 2020. Instead, the “Katowice Climate Package,” decision, which contains the Paris rulebook and also other sections with more political messages, merely “takes note” of the Dialogue and invites parties to consider its outcome in preparing their NDCs. Some also noted that there were fewer announcements of new climate finance than at previous COPs, which they felt indicated reduced commitment by developed countries to support ambition of developing countries.

Non-party stakeholders are considered crucial to help raise ambition both by increasing the transparency of the negotiation process and as important contributors to climate action. Many observers lamented the fact that the entire second week of negotiations unfolded behind closed doors with few reports back from the ministerial consultations. Some also noted a diminished focus on the Global Climate Action Agenda, kickstarted in 2014 to orchestrate broad coalitions of the willing and incorporate these actors into the formerly exclusively intergovernmental regime. While diminished transparency may have been necessary to allow for resolution of the most politically-difficult issues at this COP, some expressed doubts about the UNFCCC’s ability to institutionalize the participation of a broader set of actors in the longer term.

Vulnerable countries, in particular, also hoped for political signals on determination to keep global warming below 1.5°C, considered a question of survival by many small island states. In this regard, resistance by four countries – Saudi Arabia, the US, Russia, and Kuwait – to “welcome” the IPCC Special Report on 1.5°C during the first week created a media tsunami, which may have compensated for the lack of strong language on the report in the final package decision. The least developed countries and small island developing states were also disappointed with what they described as continued sidelining of the issue of loss and damage and stressed the urgency to provide real financial support.

The Katowice COP delivered on its mandate and now parties must turn the page to a new era of implementation and higher ambition. As noted by UN Secretary-General António Guterres, in a speech read at the closing of the conference by UNFCCC Executive Secretary Patricia Espinosa: the priorities now are “ambition, ambition, ambition, ambition, and ambition,” on mitigation, adaptation, finance, technological cooperation, capacity building, and innovation. In this regard, many delegates left Katowice feeling cautiously uplifted, looking ahead to 2019 when the UN Secretary-General, who personally facilitated the negotiations during the second week, will hold a Climate Summit to raise ambition ahead of the crucial year of 2020, when many countries will deliver updated NDCs and the Paris Agreement will face its first true litmus test.