Currently, only three countries are producing shale gas through hydraulic fracturing (fracking) on a commercial scale: the United States, Canada, and China. But as several other countries undertake shale resource exploration efforts, a key question remains: What are the impacts of shale gas mining on local economies and the environment? In the Worldwatch Institute’s latest Vital Sign, Research Fellow Christoph von Friedeburg concludes that any strong national reliance on shale gas (domestic or foreign) could have undesirable consequences in both the near and long term.

Worldwide, an estimated 7,299 trillion cubic feet of shale gas is considered “technically recoverable.” However, continued exploration could lead to substantial revisions of deposits that are not merely technically, but also economically recoverable.

Worldwide, an estimated 7,299 trillion cubic feet of shale gas is considered “technically recoverable.” However, continued exploration could lead to substantial revisions of deposits that are not merely technically, but also economically recoverable.

Discussions about fracking are ongoing in several European countries, including Germany, the United Kingdom, and Bulgaria. But recoverable quantities of shale gas across the region remain uncertain, and many supplies are located deep underground, some in densely populated areas. Additional factors inhibiting the development of Europe’s shale gas resources include disputes about the ownership of mineral rights, and substantial environmental and safety concerns.

The U.K. government appears to be in favour of shale gas development. However, the single shale well that has been fracked in the country so far, in 2011, caused two earth tremors, leading to a temporary ban on fracking that was in effect until 2012. Since then, a handful of exploration wells have been drilled, but none have been fracked so far. In Romania, expectations for the country’s shale gas future have soured because of lower and less-profitable projections of available reserves, growing public opposition to fracking, and lower oil prices, which have rendered natural gas less economically viable.

China has invested more than $1 billion in shale gas exploration so far. But most of the country’s deposits are located in hard-to-access mountainous areas, either at great depths or too far from the considerable water resources required for the fracking process. This makes drilling wells, as well as establishing the needed infrastructure, such as roads and pipelines, more challenging and expensive.

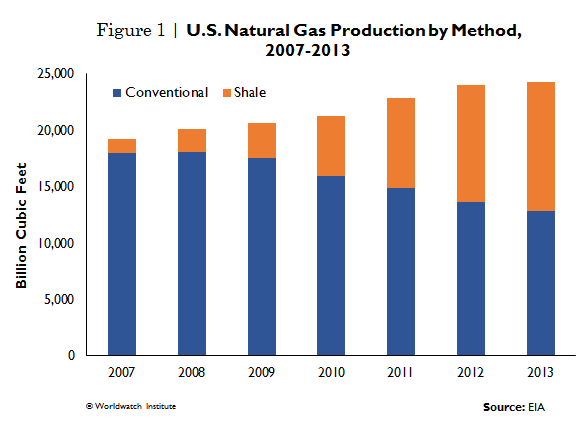

The United States is by far the dominant producer of shale gas, producing a record 32.9 billion cubic feet per day in 2014. Proponents of fracking have touted shale gas development as a boon for local job creation. However, most of the associated jobs are temporary, and many are filled by out-of-area workers whose short-lived influx provides only passing benefit to local economies. The development of clean, renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar, has been shown in many cases to be more successful in creating employment.

The costs of damages to local roads from the heavy-truck fleets needed for well construction and wastewater transport amount to hundreds of millions of dollars. Air pollution emissions from vehicles and from well-pad diesel generators can harm human health. And the toxic wastewater that flows out from the wells after the fracking fluid is pumped underground-containing a mixture of chemicals, water, and sand-is often inadequately treated, presenting a danger to soils and aquifers. Such impacts need to be assessed closely within the United States as well as in other countries that are considering shale gas development.

The shift in the United States from coal to natural gas for power generation has helped to reduce domestic greenhouse gas emissions in the short term. But the long-term, global benefit of this reduction is dubious, as fracking releases large quantities of methane-a more potent contributor to atmospheric warming than carbon dioxide-and because growing amounts of U.S. coal have found their way to export markets. Furthermore, optimistic projections of future U.S. shale gas production have been called into question.