Landmark Convention on Biological Diversity decision calls on governments to conduct strict risk assessments and seek indigenous and local peoples’ consent ahead of potential release of “exterminator” technology

The UN on Thursday, November 29, 2018 made a significant global decision on how to govern a presumably high-risk new genetic engineering technology – gene drives.

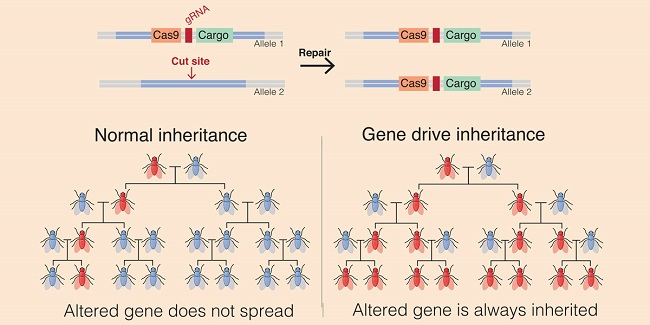

A gene drive is a genetic engineering technology that can propagate a particular suite of genes throughout a population. Gene drives can arise through a variety of mechanisms. They have been proposed to provide an effective means of genetically modifying specific populations and entire species.

“This important decision puts controls on gene drives using simple common-sense principles: Don’t mess with someone else’s environment, territories and rights without their consent,” explains Jim Thomas, co-executive director of the ETC Group. “Gene drives are currently being pursued by powerful military and agribusiness interests and a few wealthy individuals. This UN decision puts the power back in the hands of local communities, in particular indigenous peoples, to step on the brakes on this exterminator technology.”

The Convention on Biological Diversity decision also requires that, before an environmental gene drive release, a thorough risk assessment is carried out. With most countries lacking a regulatory system for the technology, it requires that new safety measures are put in place to prevent potential adverse effects. The decision acknowledges that more studies and research on impacts of gene drives are needed, to develop guidelines to assess gene drive organisms before they are considered for release.

“In Africa we are all potentially affected, and we do not want to be lab rats for this exterminator technology,” notes Mariann Bassey-Orovwuje of Friends of the Earth Africa and chair of the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa. “Farmers have already marched in the streets of Burkina Faso to protest genetically engineered mosquitoes and we will march again if they ignore this UN decision. We are giving notice now that potentially affected West African communities have not given their consent or approval to this risky technology.”

The agreement to seek and obtain consent may immediately impact the most high-profile (and well-funded) gene drive project, by researchers at London’s Imperial College, who aim to release genetically engineered mosquitoes in Burkina Faso as a step towards future gene drive mosquito releases. Contrary to Target Malaria’s claims, people living in the villages targeted for potential release have not been consulted or given consent.

This decision follows a campaign by hundreds of organisations, along with concerns expressed by several governments represented at the UN, who called for a moratorium on the environmental release of gene drives.

The globally-agreed decision requires that governments must seek the approval of “potentially affected indigenous peoples and local communities” prior to considering any release of gene drives, including experimental releases. Given that gene drives are designed to spread through a species and across geographic regions – a novel feature of this form of genetic engineering – any environmental release could potentially affect communities far beyond the single release site and it will now be necessary to seek wider consent. This puts an important halt to gene drive releases moving forward. The UN decision, it was gathered, justifies controls on gene drive releases because of their potential impact on the “traditional knowledge, innovation, practices, livelihood and use of land and water” of Indigenous peoples and local communities.

Guy Kastler from La Via Campesina, a global movement that represents over 200 million peasants from 182 organisations in 81 countries, said: “The prospect of this technology brings unprecedented risks that we can’t accept. The UN should have decided a clear moratorium on gene drives. La Via Campesina calls on peasants of the world to oppose in every country the implementation of this technology, which can potentially exterminate our crops or animals and other elements of biodiversity essential to our productions and livelihood.”

Research reported this week has shown that Anopheles mosquitos (one of the insects that carry the malaria parasite) may routinely be blown long distances across Africa by winds at upper atmospheric levels. This could potentially expand the geographic area of “potentially affected” Indigenous peoples and local communities to the entire continent.

The UN decision comes in the same week that the Cayman Islands decided to end trials of experimental genetically engineered mosquitoes amid reports that infectious mosquito populations increased instead of declining. Caribbean countries were among those supporting a moratorium on gene drives.

Besides the requirement for consent, the conditions require that risk assessments are carried out and risk management measures put in place “to avoid or minimise potential adverse affects”.

The decision recognises that, before these organisms are considered for release into the environment, more research and analysis are needed, and the UN should develop specific guidance to evaluate potential impacts on biodiversity and communities.

Such guidance is now agreed to be developed through a “Risk Assessment Ad Hoc Technical Expert Group”, established on Thursday under another decision. Because the development of formal risk assessment guidance is set to take some years, this part of the decision may also practically act as a further brake on the release of gene drive organisms.