The first decade of the 21st century was ripe with discoveries and innovations in the animal kingdom. From 2001 to 2010, new species were found, ground-breaking animal research was published, and some species were brought back from the brink of extinction. But the past 10 years also saw some animals wiped from existence.

Here’s a look at the species that were declared extinct this decade, with the West African black rhino topping the list.

West African black rhino

The rarest of the black rhino subspecies, the West African black rhinoceros, is now recognised by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as extinct. The species, Diceros bicornis longpipes, was once widespread in central Africa, but the population began a steep decline due to poaching. The rhino was listed as “critically endangered” in 2008, but a survey of the animal’s last remaining habitat in northern Cameroon failed to find any sign of the rhinos, either a true siting or even evidence of its presence, like feces or feeding signs. No West African black rhinos are known to be held in captivity.

Baiji dolphin

The last documented sighting of China’s baiji dolphin, or Yantze River dolphin, was in 2002, and while the species is listed as critically endangered, scientists say it may already be extinct. In 2006, scientists from the Baiji Foundation travelled up the Yangtze River for more than 2,000 miles equipped with optical instruments and underwater microphones, but were unable to detect any surviving dolphins. The foundation published a report on the expedition and declared the animal functionally extinct, meaning too few potential breeding pairs remained to ensure the species’ survival.

The decline in the baiji dolphin population is attributed to a variety of factors including overfishing, boat traffic, habitat loss, pollution and poaching. Deemed “the goddess of the river,” the dolphin’s skin was highly valuable and used to make gloves and handbags.

Golden toad

The golden toad, which is sometimes referred to as the Monteverde toad or the orange toad, was a species that lived only in the Monteverde Cloud Forest Biological Reserve in Costa Rica. It was once a common species, but no specimen has been seen since 1989. The toad’s breeding sites were well-known and closely watched — in 1988, only eight males and two females could be found, and in 1989, only a single male could be located. Extensive searches for the golden toad since then have failed to locate another specimen, and the species was declared extinct in August 2007. The amphibian disease chytridiomycosis, airborne pollution and global warming probably contributed to the species’ demise.

Hawaiian crow

This native Hawaiian bird was declared “extinct in the wild” in 2002 when the last two known wild individuals disappeared. Some birds remain in captivity, and between 1993 and 1999, more than 40 birds were hatched in a captive breeding program. The birds were released into a lightly managed habitat and closely monitored, but releases were abandoned in 1999 because of increasing mortality. A reintroduction plan is being developed, but about 75 Hawaiian crows would be needed for the plan to work. The reasons for the bird’s extinction is not fully understood, but researchers speculate that an introduced disease, such as avian malaria, might have played a significant role in the species’ decline.

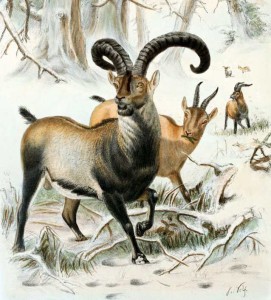

Pyrenean ibex

The Pyrenean ibex is one of two extinct subspecies of the Spanish ibex. The species was once numerous and roamed across France and Spain, but by the early 1900s its numbers had fallen to fewer than 100. The last Pyrenean ibex, a female nicknamed Celia, was found dead in northern Spain on Jan. 6, 2000, killed by a falling tree. Scientists took skin cells from the animal’s ear and preserved them in liquid nitrogen, and in 2009 an ibex was cloned, making it the first species to become “unextinct.” However, the clone died just seven minutes later due to lung defects.

What caused the Pyrenean ibex’s extinction remains unknown, but some hypotheses include poaching, diseases and the inability to compete with other species for food.

Spix’s macaw

Although 71 Spix’s macaws exist in captivity (like the two pictures here), the last known bird in the wild disappeared in 2000 and no others are known to remain. The species is currently listed as “critically endangered” instead of “extinct in the wild” because not all areas of potential habitat have been thoroughly surveyed. The bird is native to northern Brazil and in 1987 the three known remaining birds were captured for trade. However, a single male bird was discovered in 1990 and paired with a female bird in captivity, but seven weeks after the female’s release, she collided with a power line and died.

The decline of the Spix’s macaw is attributed to hunting and trapping, habitat destruction and the introduction of Africanised bees, or “killer bees,” which compete for nesting sites.

Liverpool pigeon

The Liverpool pigeon, or spotted green pigeon, is an extinct bird species of unknown origin, although some researchers speculate it might have lived in Tahiti. The only remaining specimen of the bird resides in the Merseyside County Museum, and scientists say it’s likely that the species was close to extinction before European exploration began in the Pacific. The International Union for Conservation of Nature assessed the species in 2008 and declared it extinct, but the reasons for its extinction remain unknown.

Black-faced honeycreeper

The black-faced honeycreeper, or po’o-uli, is endemic to Hawaii’s island of Maui and is listed as “critically endangered/possibly extinct.” Of the three known birds discovered in 1998, one died in captivity in 2004 and the remaining two have not been seen since that year. Scientists say the species may already be extinct, but surveys in all areas of potential habitat are needed to confirm this. If any have survived, the population would be extremely small. Habitat destruction and the rapid spread of disease-carrying mosquitoes are thought to be responsible for the species’ decline.

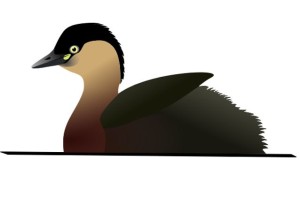

Alaotra grebe

The alaotra grebe, which is also known as a Delacour’s little grebe or a rusty grebe, was declared extinct in 2010, although it might have been extinct years earlier. Scientists were hesitant to write the small bird off too soon because it lived in Lake Alaotra, which is located in a remote part of Madagascar. Thorough surveys of the area in 1989, 2004 and 2009 failed to find any evidence of the species, and the last confirmed sighting of the bird was in 1982.

The alaotra grebe population began to decline in the 20th century because of habitat destruction and because the few remaining birds started mating with little grebes, creating a hybrid species. Considering the bird’s restricted range and lack of mobility, scientists declared it extinct, and today, only one photograph exists of an alotra grebe in the wild.

Holdridge’s toad

The Holdridge’s toad was a species endemic to the rainforests of Costa Rica. While it was declared extinct in 2004 because the animal has not been seen since 1986, surveys in 2012 resulted in the toad’s status being upgraded to critically endangered. Its population size is likely less than 50 individual toads. The main cause of the toad’s population decline and extinction is likely chytridiomycosis, an amphibian disease, perhaps in collaboration with the effects of climate change.